As Valley housing crisis escalates, so do the numbers of Airbnbs

By Eric Valentine

When former Valley resident Mark Oliver announced he’d be closing down his Ketchum-based hotel and entertainment venue known as the Hot Water Inn, he left a massive Facebook post that was largely positive and grateful. But the post from April 2019 also contained a sincere warning:

“This leads me to the lack of housing, VRBO, AirBnB and Homeaway,” Oliver wrote in his Dear John. “If you own a rental and currently do this, I don’t fault you for doing so, but know doing this is killing this town.”

While it’s a stretch to call Oliver’s words prophetic—every resort town has for years been dealing with similar affordability issues when it comes to housing its working class—it’s not a stretch to say the Valley’s housing challenges have become the Valley’s housing crisis. Mayors and other leaders here are making regional and national news for considering “tent cities” as a band-aid to the issue. A July issue of “The Wall Street Journal” had this headline and underride: “Ketchum, Idaho, Has Plenty of Available Jobs, but Workers Can’t Afford Housing: Businesses in the town, near the Sun Valley ski resort, can’t fill openings as applicants are unable find a place to live; mayor proposed letting workers pitch tents in a park.”

Tell us something we don’t know

While the WSJ article does what WSJ articles do—craft a perfectly told journalistic story—it may not have covered the whole story. The article points out the age-old market-driven issue of how the nature of resort communities makes them expensive to reside in and how the workers who make those communities run have trouble finding affordable places to live. It even deep-dived a bit to tell the plight of Ketchum city council member Michael David, a ski shop worker, who explained that he has been staying at friends’ and relatives’ vacation homes in recent years.

What it didn’t do was dive into the issue of temporary housing apps like the ones Oliver noted; specifically, how badly has the industry impacted housing availability.

Although there’s no comprehensive or perfect metric, common sense dictates that when one residential property is put into the vacation rental market, it’s being taken out of the residential rental market. Assuming most working-class people can’t afford to live alone, and since some working-class people actually have a spouse and children, it seems 3 is a safe number to use in the following math/logic.

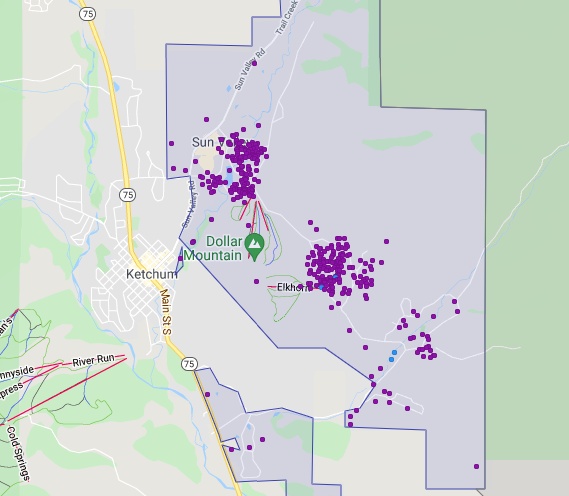

According to Airdna, a leading vacation rental data aggregator, the Valley has a total of

943 active units on apps like Airbnb, and almost all of them are entire homes, not single rooms. Multiply that by the number 3 and you get 2,829—a tad more than the total population of Ketchum. Since 3 may be a factor too high, multiply the active units on Airbnb-type apps by 2 and you get 1,886—about 500 more people than the population of Sun Valley.

Incidentally, several of those housing units not available to residents are owned by Ketchum city council member Jim Slanetz, who acknowledges “the buzz on the street” about his dabbling in Airbnb is not thought of positively. Slanetz explains that he is empathetic to renters and the challenges they face, but says, overall, he has actually added to the local housing supply.

“I’ve created more housing than I’ve taken,” explains Slanetz.

That’s in part because Slanetz has built single-family dwellings that he says he rents out long-term to residents. And attached to his personal residence are two additional dwelling units that are also rented out long-term to residents.

“I basically live in a triplex where everyone renting here lives here,” Slanetz said.

Interestingly, two of Slanetz’s Airbnbs today are not standard dwelling units anyway. They are treehouses, which were built almost a decade ago, Slanetz said, so that the rental income from them made it possible for him to make a life in the Valley pencil out.

“I invested in this town. I didn’t have a ton of money coming here but I took a chance and it worked out,” Slanetz said.

As for the traditional residential units of his that are off the residential market and on the Airbnb active list, Slanetz said those are all in the community core, which is zoned to be commercial or residential and in a resort town is understood to be largely short-term vacation spots, not working-class housing solutions.

“I could turn those into a bar” or some other kind of establishment, Slanetz points out, but instead he is providing places to stay for people who end up frequenting businesses here.

The math spells a big problem

Nonetheless, the dilemma is still real. And it leads to the question: What can a city do about it?

Just last week, Ketchum officials met with city leaders from Vail, Colorado, who faced—and got one step ahead of, at least—the same housing problem. They enacted and funded a law that paid residential homeowners to place deed restrictions on their units so only people in the local workforce would be allowed to live there. But it’s not clear if that would pass muster in Idaho.

“The problem lies at the state level,” Slanetz said. “Pressure needs to be placed there.”

Slanetz is referring to the 2017 Idaho law on land use planning that prohibited local jurisdictions from denying people the right to list on Airbnb.

“Neither a county nor a city may enact or enforce any ordinance that has the express or practical effect of prohibiting short-term rentals or vacation rentals in the county or city,” the law states. It adds, “Neither a county nor a city can regulate the operation of a short-term rental marketplace.”

But it hasn’t stopped Ketchum from taking action.

“I am delighted that the council supported our proposal to permit recreational vehicles (RVs) to be used as temporary housing on private land,” wrote Ketchum mayor Neil Bradshaw.

Permits will be required for qualified workers to live in an RV.

The council also supported looking into regulation of short-term rentals by focus

No Vacancy

A look at each Valley city’s number of active rentals on Airbnb and other temporary housing apps:

Sun Valley: 351

Ketchum: 482

Hailey: 82

Bellevue: 20

Fairfield: 8

Carey and Picabo data unavailable.

Source: Airdna