BY LARRY BARNES

A heavy drizzle came and we sought refuge in a quartet-sized amphitheater made by water and time in Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. The plateau 1,000 feet above us captured the water where it gathered into rivulets on slickrock and ran down to black vertical streaks in the Kayenta Formation rising around us. The rain stopped and we stepped into the open, the brightening sky, the singing canyon wrens, and continued toward our camp at the confluence a mile down canyon.

The generous snows of 2022-2023 foretold a brief springtime pulse of water that might fill the Escalante River with enough water to carry small watercraft down its length to the river’s end, Lake Powell. After paddling our inflatable kayaks a few hundred yards downstream, the three of us became committed to the entire 10-day float. But southern Utah was thirsty and stingy with its melting snows, and little water reached the muddy Escalante. For the next 80 miles, the river, “too thick to drink, and too thin to plow,” concealed the rocks and mud bars that were just below our fingertips.

There were a few rapids and occasional dry-mouthed fear but there was mostly deep concentration in reading the water, reading between the lines, divining the subtext, and even using Braille with our paddles to predict the river’s depth and seek the deepest channel to avoid sudden bumps, lurching stops, and subsequent dragging, pushing, and cursing. There were others on the river, too, and they used packrafts, tiny high-tech, expensive pool toys, often technicolored and traveling in whirligig pods of 5-10. Their occupants over-used the word “literally,” encouraged their mates to “send it,” and lacked gray hair. Our boats weighed three to four times more than theirs and frequently got stranded in the shallow water. We were using film in a digital age. It’s strange to be within the age class that the whirligig tribe might call old.

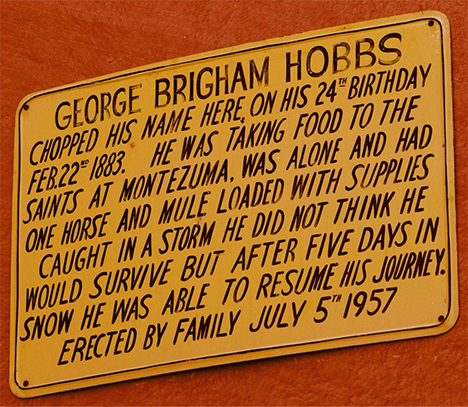

But looking up to the red cliffs leaning over us 1,000 feet, and we are all the same age; fellow travelers in a nanosecond of time through rock that formed 200 million years ago. Even pioneer George Brigham Hobbs, contemplating his mortality 140 years earlier when stranded by winter snow in Silver Canyon, was a traveler in the same time frame — at least in the Kayenta Formation scale, one having deeper meaning than the blink of a human life.

While the rock has changed little and the canyons have only grown a few millimeters deeper since George Brigham Hobbs chopped his name into the rock, other changes have been profound. We wondered what Mr. Hobbs, a Mormon settler, would have found most astonishing about the changes since he nearly froze in 1883. That today, for a few days’ wages, he could fly across America in machines that make straight white lines in the sky. That still, after 140 years into these latter days, there has been no Second Coming. That today we carry devices in our pockets that communicate with the world through the ether. That today you could be fined for hacking your initials into these very rocks. Or that travelers now must carry their solid human waste with them down the river and out of the canyon in “wag bags.”

Upon leaving the quartet amphitheater I realized that I had forgotten my water filter and turned to walk back up the dry wash. But there was soon an alarming sound, a sudden realization, and an angry front of muddy churning water, blackish with cream-colored froth on its leading edge. A quick scramble to higher ground and there below me the flash flood grew into a chocolate milkshake river, carrying the land to the sea.

Two time scales had collided. To the Kayenta Formation, this was a trivial event, one that happened with monotonous regularity over the previous 200 million years, during which these canyons had been carved. To the nanosecond human scale, this was a marvel of a lifetime.

All historic times were special to the people who lived through them, but the last 140 years were extra special. Earth is rapidly heating and its human population has doubled three times. Novel challenges await us in the next 140 years. But as long as the sun burns, geologic periods will come and go and life on Earth, in some form, will continue.

Larry Barnes retired from 26 years as a biology teacher at Wood River High School and is now transitioning to spending more time exploring the natural world.