While ICUs battled the most severe cases, other COVID-19 healthcare providers dug in too

By Eric Valentine

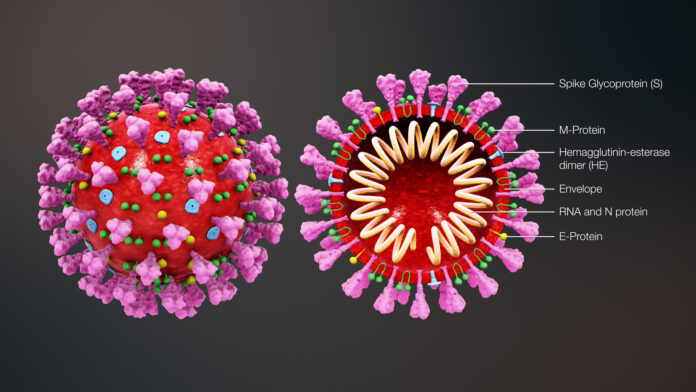

Photo credit: Karen Stevens

President Donald Trump has called it “the invisible enemy,” among other things. And while charts of case numbers and death tolls as well as images of mask-wearing healthcare workers and grocery shoppers flow freely, something we don’t always see is what goes on behind the COVID battles along the periphery—the healthcare providers not inside the Intensive Care Units.

We spoke with two people about their firsthand experience with the novel coronavirus: a nurse at St. Luke’s and a private-practice physician’s assistant.

The Nurse

For Karen Stevens, the assistant nurse manager for St. Luke’s Health System, a pandemic is nothing new. She began her healthcare career in the 1980s, when the HIV-AIDS epidemic was surging. And while the viruses have their distinct differences, Stevens acknowledges how similar the circumstances are when it comes to providing care.

“It was the not-knowing that was so hard. That’s the challenge with novel viruses. We had a demographic of affected people but we didn’t have all the information (such as how the virus was transmitted and how contagious it may or may not be),” Stevens observed. “It took years to get it right.”

The getting it right part isn’t about the diagnosis and the treatment; for a nurse like Stevens, it has to do with how to triage patients and how to provide care in the best possible way without spreading the disease. With the recent COVID-19 crisis, St. Luke’s was more of a testing and ER than it was an Intensive Care Unit. Patients that needed ICU were transferred to Twin Falls and Boise. But before someone would get transported, they’d be under the care of multiple doctors and nurses, all of whom needed to wear far more PPE (personal protective equipment) than in normal circumstances. And with every new patient, there needed to be new PPE put on, too.

“We’re used to providing care,” Stevens said. “It’s the ‘change fatigue’ that can set in, too.”

Change fatigue refers to the procedural changes (not just the changing out of PPE) that can happen weekly and even daily in healthcare when new guidelines come down from the CDC on how best to protect the spread of a disease.

There is some positive impact in all of this. Stevens noted that normally nurses specialize in a particular department and type of care. But given the reconfiguration St. Luke’s had to go through to handle the pandemic, nurses had to work across departments.

“I think it made us better healthcare providers,” Stevens said. “Individually, we have always had a great team of doctors and nurses. But the reconfiguring made us a better team.”

The Private Practitioner

For Nanette Ford, a physician assistant who has been practicing in the Valley for 24 years, there has been a combination of frustration and elation.

“I can barely get masks and gloves. I was able to order four boxes of gloves last week. I couldn’t get masks,” Ford said as she explained one of the reasons she can’t provide COVID-19 testing and treatment in her office. “I have to turn away patients with acute symptoms, and to a healthcare provider, that feels like a mortal sin.”

But Ford can—and does—provide antibody testing. The particular test she performs is a blood draw and has the highest possible accuracy rating.

“That has been a godsend,” Ford said.

The antibody test can be performed on an unlimited basis, unlike the COVID-19 diagnostic test, and it tells a patient if they have built up antibodies known to fight the virus. It’s the test most people hope to be positive.

“Most of them (patients with antibodies) start doing the happy dance,” Ford said.

Like Stevens, Ford noted that so much is still unknown about the virus. That means we’re optimistically assuming that the antibodies will do two things: 1) Protect us from the virus, and 2) Stick around long enough to protect us from the virus down the road.

“Testing again in the fall or winter would help us see if the antibodies are still holding,” Ford said.

Also like Stevens, Ford said the pandemic has led to positives (other than test results). She noted how private practitioners are all coordinating and sharing information with one another regularly. In fact, one person providing the medical community with the latest data is a retired doctor, Scott McLean.

We Haven’t Won Yet

Although caseloads have gone down in the Valley and as businesses slowly reopen, both Stevens and Ford said if there was one thing they could let the community know, it is that we’re not out of the woods yet.

Regarding the recent protests, Ford said, “People are risking their lives to be heard right now, and I don’t have any judgment on that.”

Regarding a recent trip to the grocery store, Stevens said, “I noticed fewer masks, less distancing. I worry that we’re letting our guard down a little and it’s not yet time to do that.”