BY HANNES THUM

Science gets a bad rap, sometimes. It has a reputation for being full of facts and figures and tables and terms that seem organized to be shoved down the throats of frightened, overwhelmed students until they want to barf.

Science gets a bad rap, sometimes. It has a reputation for being full of facts and figures and tables and terms that seem organized to be shoved down the throats of frightened, overwhelmed students until they want to barf.

I have heard it, repeatedly: science is too serious, too hard, and too complicated. That it’s intimidating, that only “science-y” people can understand it, and the rest of us are doomed to be excluded from some inner circle of scientific knowledge (in this way, it reminds me of Western music theory).

Why memorize the periodic table? Because you are supposed to. Why learn what the endoplasmic reticulum does? Because it’ll be on a test. Why do the math to find the apogee of a planet’s orbit? Because you might need it one day (if you work for NASA).

The truth is that science is way more about asking questions than having answers.

And, I like it best when it reminds me of Calvin’s adventures from the incomparable Calvin and Hobbes comics. Remember when he used to go to Mars? When he built his Transmogrifier? His Cerebral Enhance-o-Tron? The Invisible Cretinizer?

Being a teacher of young students must be one of the greatest Invisible Perspective Enhancers in all of science. It reminds me, daily, that science starts with imagination and curiosity. If it also needs tedious legwork to get anything done, all of that should come after the question-asking.

A couple of weeks ago, scientists published the latest round of data and papers from the Parker Solar Probe that is currently flying at screaming speeds (the fastest ever for a spacecraft) toward and around the Sun. There is some really weird stuff that goes on when you get close to the sun, it turns out. Calvin would be proud of whomever dreamt this mission up.

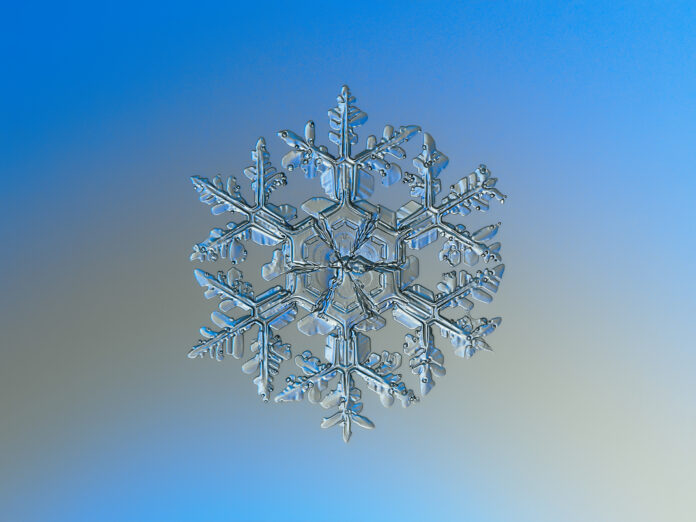

Are no two snowflakes alike? We’ve been told that, over and over. So, is it true? Probably, I gather—most scientists figure that the chances are more or less infinitely small that two snowflakes could be alike, molecule for molecule. But, that hasn’t stopped a scientist or two from trying to grow identical snowflakes in a lab. And here’s what I find fascinating: why on Earth would we need to know the answer to this question? There’s not a realistic reason, I’d argue, other than to answer a question that tickles our imagination. Again, Calvin would be proud.

I don’t want to be dismissive of those scientists who have put in their years of laborious and technical work to use the periodic tables and their knowledge of apogees (and, maybe, endoplasmic reticula) to uncover mysteries of the universe. They have given us the gifts of things like photos from Hubble and vaccines and computers to connect us. We should be grateful.

But, I hope we cannot lose sight of where science came from. It came from asking questions, about everything from the Sun to snowflakes. And everybody can do that.