BY HANNES THUM

Ah! The signs of summer. Kestrels perched on power lines, scanning the fields. The elk and deer slowly regrowing their antlers. Insects of a dizzying array rising up from the riparian areas each evening, each species in their turn, and the fish rising to meet them. Plants filling out their greenery to maximum capacity.

Folks often talk about the “dog days of summer” at this time of year. Like many people, I spent a lot of my life thinking that this phrase had something to do with the neighborhood dogs napping through the day under the shade of a tree, panting in the heat with tongues lolling and ears drooping.

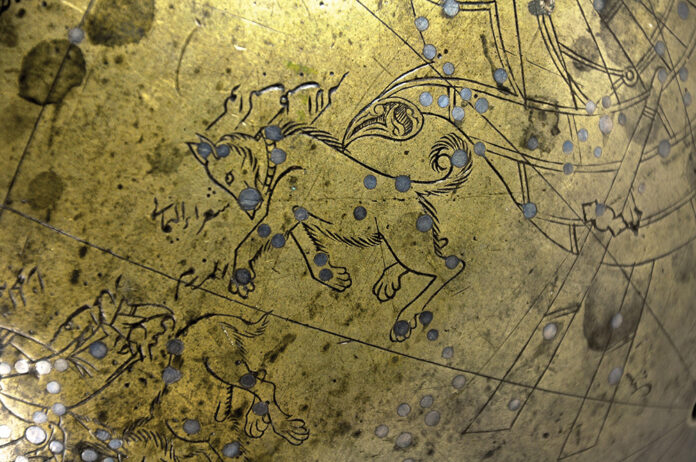

It turns out that the term refers to a star in the sky—namely, Sirius, or “the Dog Star.” Sirius, part of the Canis Major (the “Great Dog”) constellation, is the brightest star in the night sky. And, because it shows up in different ways in our sky at different times of the year, this star has long been a marker of time and seasons for us humans. Way back when, as most of our language and cultural traditions were being founded, people knew that when Sirius reached a certain place in the morning sky, summer had truly arrived. Thus, they referred to the dog days, and the phrase has stuck.

The most striking thing about the term “dog days of summer” is, indeed, the fact that the term is rooted in the observation of stars. A reminder that for the great majority of our human existence, the night sky was a major part of our lives. Before the invention of electric lighting, both inside and outside of our dwellings, and back when the annual cycle of seasons was of a more tangible and immediate importance in our lives, the stars would have been hugely important things for us to pay attention to. Their annual circuits across the sky would have given us a sense of time, and a sense of our place in the universe.

Imagine how stunning and beautiful the stars would have been to our ancestors. Firstly, the night sky would have been much more visible and vibrant (thanks to the lack of the aforementioned electric lights). Also, what else would there have been to do in the evenings? Most nights, it was probably too dark and dangerous to hunt or to move about, and there weren’t books or TV shows to draw us away from looking at the only thing there really was to look at in the nighttime: the stars themselves.

It is no wonder that human cultures have long been naming and observing stars and constellations. If our modern societies have lost that connection, it is a recent and perhaps saddening development. But, it’s an easy one to address.

On these beautiful, long summer evenings, all we need to do is stay awake, look for those first stars to appear in the sky at dusk and try for just a little while to picture all of the movement that our universe is constantly undergoing around us.

Hannes Thum is a Wood River Valley native and has spent most of his life exploring what our local ecosystems have to offer. He currently teaches science at Sun Valley Community School.