Proposal For Idaho’s First Nuclear Plant Takes Shape

BY Mark Dee

In a shift that mirrors federal priorities, a nuclear power plant may find a home in southern Idaho at a site slated for a wind farm as recently as last year.

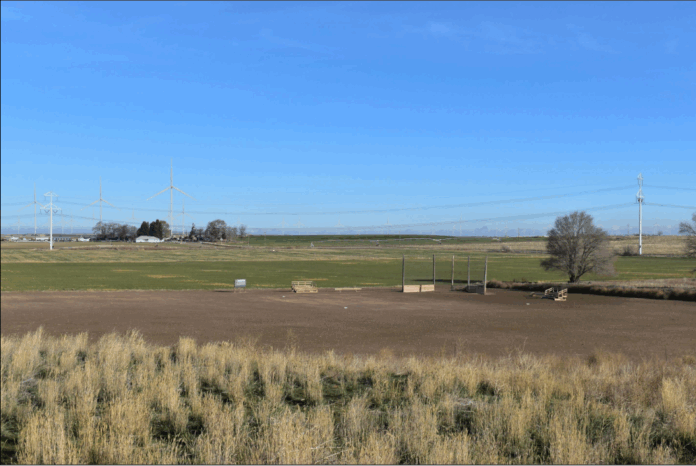

Sawtooth Energy and Development is eyeing 320 acres of public land in northwest Jerome County for a nuclear facility. The site sits on the corner of the roughly 100,000 acres previously slated to house the 241-windmill Lava Ridge Wind Project proposed by Magic Valley Energy. While the Bureau of Land Management greenlit a version of the wind project in December, President Donald Trump froze development via executive order on the first day of office.

Now, Sawtooth Energy is working towards developing Trump’s preferred power source—nuclear—on a portion of the same land. Spurred by financial incentives and buoyed by deregulation around commercial nuclear reactors, the Pocatello-based firm expects to submit a preliminary plan to the BLM as soon as next month, according to Project Manager Dan Adamson.

“Nine out of ten things have fallen towards nuclear,” Adamson said. “They’ve made doing a draft environmental impact statement ten times easier. They have put more grant money to work, and interest deductions, and federal tax credits. The whole attitude of the president towards nuclear kind of says it all.”

If approved, the plant would be the first commercial nuclear facility in Idaho, and one of the first in the nation to use small modular reactors, a nascent technology that can be built in factories and assembled on site, cutting construction costs and saving time. Sawtooth Energy’s preliminary plan is to buy six of them, which Adamson expects to produce enough electricity to power 400,000 homes. While substantial, that’s less power than would have come out of Magic Valley’s wind proposal, even after the BLM cut the proposal in half in the face of public opposition.

Adamson says that nuclear has two advantages over wind. First, the plant’s footprint—40 developed acres within a 320-acre safety buffer—is considerably smaller than the roughly 104,000 acres set aside for the Lava Ridge plan, which would have disturbed nearly 5,000 acres for windmills. Second, the reactors can run 90% of the time, whereas windmills can only generate power when windspeeds are right.

There are downsides, too. Chief among them: Small modular reactors simply don’t exist in the U.S, and are likely years away from domestic use. Two plants use versions of these systems worldwide, one in Russia and another in China, according to industry outlets. In America, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission recently approved the design of Sawtooth Energy’s preferred model, but the vendor, NuScale, still targets 2030 for deployment, according to reporting from Reuters.

Then, there’s the fuel. While the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has a courier service for delivering radioactive materials, there’s no permanent national repository for spent fuel; that means spent nuclear rods live in vaults onsite at all plants nationwide, Adamson said. Sawtooth Energy’s plan would be built to federal safety specs, Adamson said, with capacity for about 20 years of nuclear material. Idaho Power, which has a plan to transition to entirely “clean” energy by 2045, considers nuclear energy clean because it doesn’t emit any carbon dioxide, according to spokesman Sven Berg, but “some experts do not consider it renewable or green due to other considerations” like spent fuel disposal.

Berg said that Idaho Power hasn’t analyzed Sawtooth’s proposal, though ultimately the plant’s power would most likely run through the company’s infrastructure. The appeal of the site is its proximity to the Midpoint Substation, a key distribution site, which Idaho Power co-owns with PacifiCorp, an Oregon-based utility.

“It is one of the most important electrical hubs in the Mountain West,” Berg said. “Energy generated all over the western U.S. goes through it to utilities and customers all over the West.”

Adamson called it “one of the largest substations in the world.”

“It’s not just a teeny thing,” he said.

Sawtooth Energy’s chosen site is 2.75 miles from the transmission hub, which significantly cuts costs, Adamson said.

“We’ll put in 10 towers instead of several hundred towers if we were going to a further substation,” he said.

From there, the power will be brokered to buyers throughout the west via a process called “wheeling,” with Idaho Power taking a fee as it sends the electricity through its transmission infrastructure.

“Broadly speaking, Idaho Power supports nuclear and small modular reactors for electric generation when it is affordable for our customers, and when we have a clear notion of how long a small modular reactor for electric generation will take to develop for commercial purposes,” Berg said in a statement. “Idaho Power receives many requests from third-party developers seeking to develop generation projects and connect them to the electric grid. These developers can work through the federally mandated interconnection process to connect their projects to Idaho Power’s or other utilities’ electric grids.”

The Idaho Conservation League is also “paying close attention” to Sawtooth’s proposal, according to a statement form ICL Executive Director Justin Hayes:

“We’re open to exploring all technologies that can help Idaho reduce emissions, strengthen grid reliability, and provide affordable electricity. Nuclear energy—particularly SMRs—could play a role. But before moving forward, we must ask the right questions.”

Those concerns include safety, reliability and cost—but also concerns about the technology’s readiness and whether Sawtooth Energy, which was incorporated early this year and has no prior projects on its resume, can deliver.

“As with any major infrastructure proposal, it’s fair to ask whether the developer has the experience, resources, and partnerships to bring a project like this to life,” Hayes said. “Before the public invests significant time, it’s important to know who’s behind the proposal and whether they can follow through. After all, Idahoans will be the ones living with the results—good or bad—for decades to come.”