BY HARRY WEEKES

I was just coming to on my couch. This roused Olive from where she was sleeping on my legs. I gave her a scratch as she slid to the floor and headed to her next warm place.

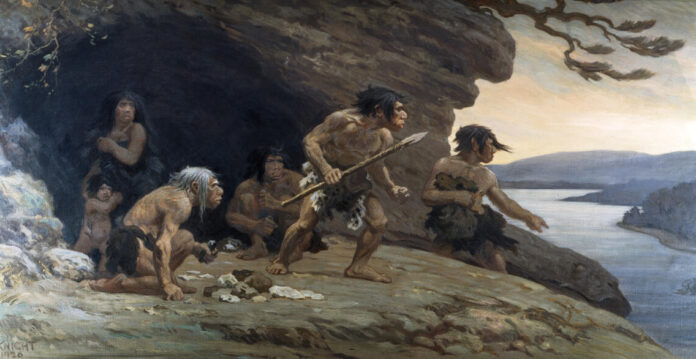

In my post-nap fog, I imagined this: “What if, at the moment the first caveperson adopted a baby wolf, which was to become the first pet, they were transported to where I was at this moment. What would he or she think?”

For starters, the wolf pup they picked up might be bigger than either of the mini-Dachshunds we have. The caveperson would recognize, vaguely, these new wolves, but would be astonished by almost everything else—their size, their shape, the fact that whenever I lie down, one or both of them climbs on me, that I tolerate and even welcome this, and that we don’t just let them sleep in our bed, we encourage it. In short, that wolves have been transformed from this massive wild companion to an “in the cave” companion.

And what about the cave?

What would be recognizable here? Certainly, the little arrangement of thyme, rosemary, basil, and mint would be understandable. These are edible. But how confused would they be when instead of going outside to collect dinner from some hastily dug hole in the snow, I open the refrigerator—our little interior ice cave completely full of all sorts of goodies? Or that now, I don’t go to the stream, but rather turn on a faucet and the stream comes to me?

So much in my immediate viewshed is easily traceable and sensical considering our human history. The lights that we turn on as soon as we get a hint of darkness. These are obvious extensions of what started as the logs burning in our fireplace.

At least one intermediate step, from burning pine to an LED, stands on the table—the candles. Our modern “fire stalks.” Imagine what it would be like to watch someone light a candle and have it burning its intense yellow and orange flame. How long would a caveperson stare at the matches? At the lighter? What would they do when I head to the cupboard and refresh one of the candles from the pile of a dozen or so lying there?

All of this would come across as a fever dream, for sure. Looking backwards, we can trace the steps. But looking forward? Even considering how Thag might describe this is comical. Imagine him coming back to the cave with a wolf. “Whoa, what are you going to do with that thing?” “This? Well, I’m going to breed it a couple hundred thousand times until it snuggles up next to me, sleeps on my lap, and comes to its name.”

But what of the orchid? The amaryllis about to bloom? The towering fig tree in the corner? There is also amazement in analyzing what we have. When did the first human start keeping plants purely for ornamental reasons? Hilary found that converting the seeds of an amaryllis back to a bulb that would yield flowers could take as long as 14 years. Who figured this out? And all to have an ephemeral spray of red, or orange, or yellow for a couple of weeks a year?

There is something wonderful and magical and astonishing… and so simply true about our desire to keep all of “this” nearby. We have houseplants, and house wolves, and we seem obsessed with keeping some element of fire nearby.

The science of our place is ultimately about keeping a connection to what it means to be human. Thinking about cavepeople and knowing that I am the future’s caveperson somehow helps me keep this connection. As do my two wolves.

Harry Weekes is the founder and head of school at The Sage School in Hailey. This is his 53rd year in the Wood River Valley, where he lives with Hilary and two mini-Dachshunds. The baby members of their flock have now become adults—Georgia and Simon are fledging in North Carolina, and Penelope is fledging in Vermont.